- Wind farm case study

Supporting the offshore wind industry with geoscience

Geoscientists from the University of Leeds are using expertise in seismic data interpretation and stratigraphy to reduce costs and to improve the lifespan of turbines for the offshore wind industry.

Using new high-resolution seismic reflection data, generated by offshore surveys, Professor Dave Hodgson and Dr Natasha Barlow and their team of researchers in the School of Earth and Environment are gaining a very detailed picture of the sedimentary environments preserved below the seabed of the North Sea. This gives wind farm companies the valuable insights needed for positioning new turbines securely on the variable sediments and mobile sea floor.

The team’s expertise in stratigraphy (the age and sequence of the geological record), seismic interpretation and paleoenvironments is providing key insights from the data to understand how the submerged landscapes of the North Sea evolved over the past 130,000 years.

The research has increased understanding of the processes occurring during the transition from land to marine environments, during sea level rise following the last Ice Age. The environmental changes occurring during earlier warm interglacial periods have also been investigated through the EU-funded RISeR programme led by Dr Barlow. This will help forecast, and plan for, future sea level rise along our populated coastlines.

The team have co-developed a new Joint Industry Programme (JIP) with Offshore Wind Industry partners that is open for new members. The focus of the first phase is the development of improved workflows for 3D ground models that capture geotechnical and geological data. More details on the JIP are found here.

The proposal has been co-developed with partners and is founded on detailed studies by PhD students using data from the Dogger Bank, offshore East Anglia, and offshore the Dutch coast. The team have also published on the crucial role of geoscience and geoscientists in the sustainable development of offshore wind, and the complexity of the geology below the seabed.

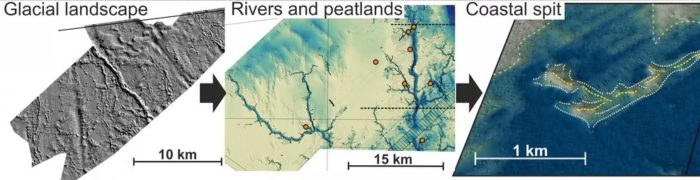

Windfarm data from the Dogger Bank reveals a wide range of submerged landscapes. A) Glacial landforms provide evidence of an ice sheet 23,000 years ago. B) The ice retreat left a low relief terrestrial landscape dissected by rivers that attracted early humans. C) Formation of a sandy spit as the landscape became coastal, prior to inundation by the sea, forcing the settlers to migrate. From Barlow and Hodgson, 2021.

A dynamic seabed environment

New industry generated seismic reflection data, available at a much higher resolution and shallower depth than that used by the oil and gas industry, are key to the research. The seismic reflection profiles form a dense 2D grid, with 100m horizontal spacing and a vertical resolution of less than 1m, for 100-200m depth. This allows the scientists to build detailed maps of former land surfaces and understand the complex depositional environments and the structure of the sediments.

The stability of the turbines is dependent on the sediments and detailed information is needed to calculate how deep turbine foundations need to go. Professor Hodgson explains “Our distinctive contribution is the understanding of the substrate and the impact this can have on the economics of installation. We are working more closely with the industry to have a stronger input on the geological controls so the best methods and materials can be chosen”.

The modern North Sea floor is a highly dynamic environment. Using the high-resolution data, the researchers have pinpointed the location of highly mobile sand bodies, which can scour at the base of the turbines. This exposes cables and decreases turbine lifespan. Decommissioning turbines is a major cost to the wind industry and has an environmental impact. Using geoscience expertise to plan for the optimal positioning of turbines, will extend their lifespan.

Offshore Wind Farm, United Kingdom.

Understanding sea-level rise

The current North Sea began to form as the ice sheets retreated 18,000 years ago, flooding lower lying areas of land with sea water. The highest area, known as Dogger Bank, remained as land until ~8,100 years ago. The seismic data shows submerged coastal barrier systems, like the Norfolk coast today, and revealed key information on how the shape of the land surface influences the path of sea water flooding. “This could inform more accurate prediction and forecasting of the rates of future sea level rise and what this might mean for low lying communities” said Professor Hodgson.

Collaboration across disciplines

Large areas of the southern North Sea were dry land for thousands of years, and archaeologists and geoscientists in the UK, Belgium and the Netherlands are collaborating with the team to discover more about how humans lived in this landscape. “The very high-resolution seismic data can really help a variety of disciplines, including archaeologists who are interested in human habitation and migration in the paleo-landscape, because these data gives much more detail than anything before” explained Dr Natasha Barlow, an expert in palaeo-landscape evolution and sea-level rise.

The interdisciplinary culture at the University of Leeds is providing opportunities for the team to work with colleagues in social sciences to find sustainable solutions to competing industries in the North Sea. “By working with colleagues with expertise on fisheries, marine planning and environmental economics we can use these data to inform different strands of science from highly applied to fundamental science” said Professor Hodgson.

“Working with ice-sheet modellers we are using the high-resolution data to understand ice-sheet dynamics in the past to inform models of how ice-sheets could behave in future” he added.

Dr Barlow said, “The overriding goal is to integrate the different strands of this work to help achieve the target of net-zero”.